Baseball’s modern contradiction would make Abner Doubleday scratch his head in confusion. The game has never been safer on paper—padded walls, advanced helmets, rule changes designed to protect the vulnerable. Yet somehow, players are hitting the Injured List at record rates. It’s like adding airbags to your car only to find yourself in more accidents.

The numbers tell a startling story. Teams paid $116 million to injured players in 1998. By 2021, that figure hit $871 million—a 750% explosion that dramatically outpaced the 300% growth in player salaries. Something doesn’t add up, and it’s costing everyone: teams, players, and fans who watch their favorite stars spend more time in rehab than on the field.

Concrete Walls and Limited Protection

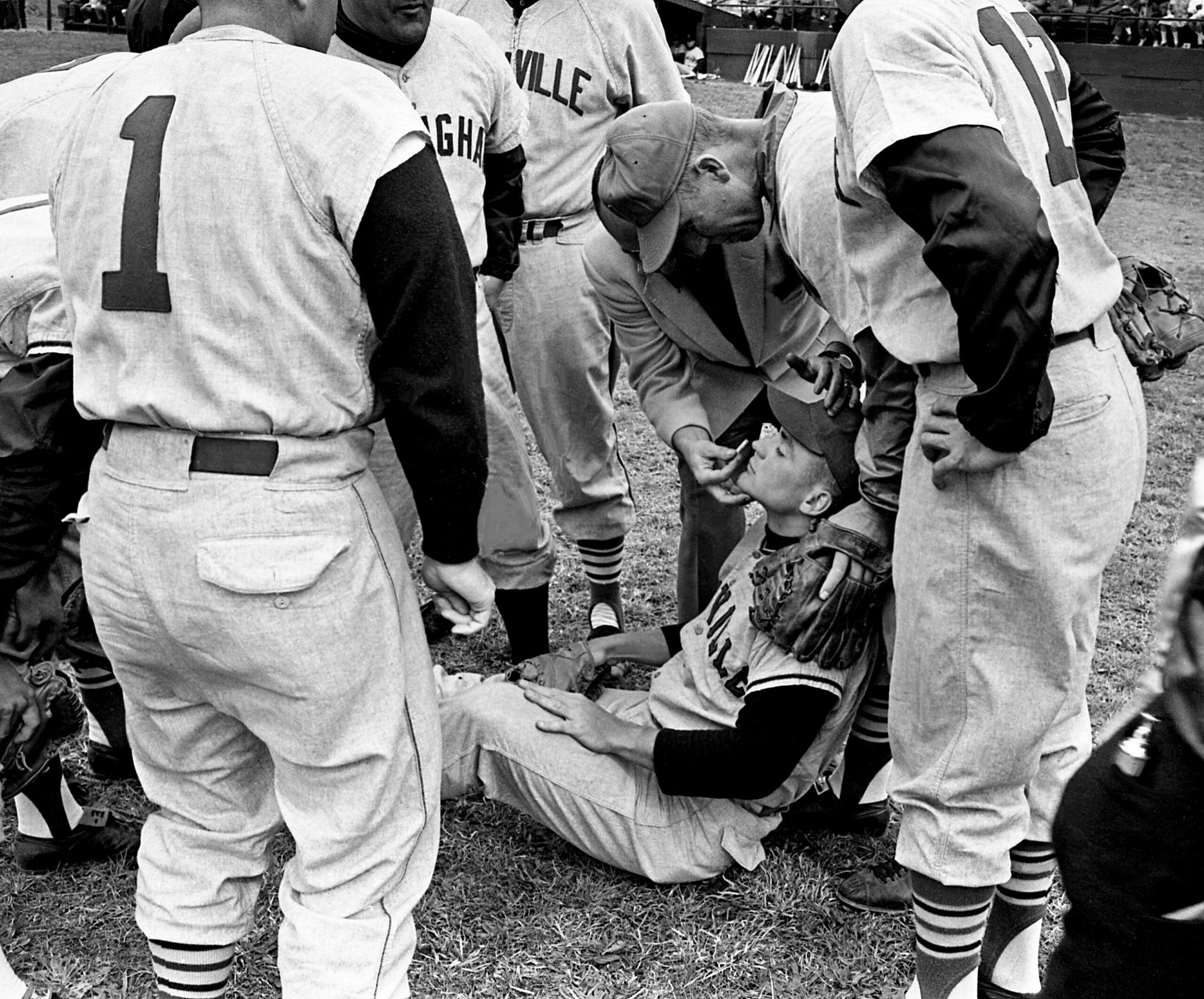

Old-school stadiums would never pass today’s safety inspections. Pete Reiser fractured his skull multiple times crashing into unforgiving concrete walls. Mickey Mantle’s promising career trajectory forever changed when his cleat caught on a drainage cover in the Yankee Stadium outfield. The game was brutal before it was beautiful.

Walk through any modern MLB stadium and you’ll see the transformation. Padded walls that compress on impact. Extended netting that protects fans from 105 mph foul balls. Dugout railings that prevent players from tumbling into concrete pits. These changes didn’t happen from goodwill—they followed catastrophic injuries and, occasionally, lawsuits that forced the game to evolve.

The Evolution of Wall Safety

Stadium walls tell baseball’s safety story better than any spreadsheet. Early parks featured concrete barriers that showed no mercy to outfielders tracking fly balls. Willie Mays famously knocked himself unconscious colliding with a chain-link fence. Turner Ward crashed through a padded wall at full speed, demonstrating that even “improved” protection had limits.

Modern walls now incorporate shock-absorbing materials that compress on impact, dispersing force away from the player’s body. These progressive resistance systems allow for deceleration rather than abrupt stopping, reducing concussion risk by approximately 40% compared to older padding systems. Still, the evolution of wall safety hasn’t reduced overall injury rates as expected.

The Rising Costs

The financial burden of baseball injuries represents a crisis hiding in plain sight. That 750% increase in injury costs since 1998 has general managers losing sleep at night. Teams operate with smaller margins than fans realize, and surprise injuries can torpedo both championship hopes and financial stability.

Teams that invest $1 million in prevention strategies (advanced biomechanics analysis, individualized training programs, and recovery facilities) average 22% fewer days lost to injury. This translates to approximately $7.2 million in saved salary expenditures annually. The math isn’t complicated, but baseball’s tradition-bound culture often resists data-driven solutions until the pain becomes too great to ignore.

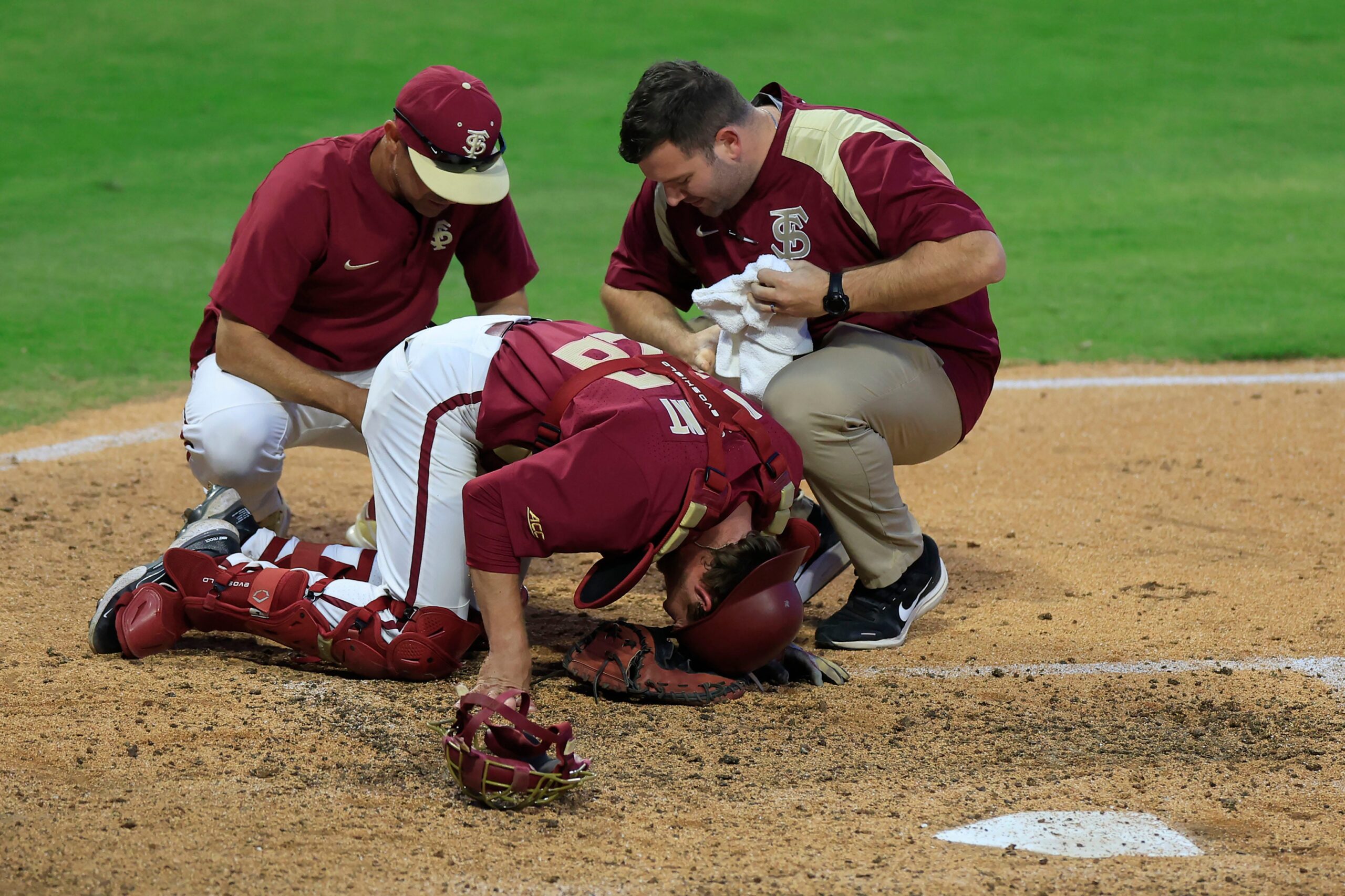

Rule Changes and Collisions at the Plate

After Scott Cousins demolished Buster Posey in a violent 2011 home plate collision, MLB finally addressed one of baseball’s most dangerous plays. The new rule prevented catchers from blocking the plate without the ball and runners from targeting catchers instead of the plate. The results speak for themselves—home plate collision injuries dropped by 45%.

The “Buster Posey Rule” demonstrates how targeted changes can preserve what makes baseball great while eliminating unnecessary danger. Youth leagues quickly adopted similar protections, recognizing that developing players lack the physical preparation for high-impact collisions. Teaching catchers proper positioning techniques reduces injury risk while maintaining competitive play.

Collisions at Second Base

Middle infielders once needed the pain tolerance of hockey goalies. The “takeout slide” was considered part of the game—until Chase Utley’s aggressive slide shattered Ruben Tejada’s leg during the 2015 NLCS. MLB responded by prohibiting runners from intentionally targeting fielders at second base, resulting in a 36% decrease in collision injuries.

Baseball’s evolution reflects our changing understanding of unnecessary violence in sports. Plays that fans once celebrated as “hard-nosed baseball” now look like reckless endangerment when viewed through contemporary eyes. The double play remains one of baseball’s most elegant defensive sequences, and protecting the athletes who execute it hasn’t diminished the game.

Sliding Injuries and Head-First Slides

Watch any MLB game and you’ll see players diving headfirst into bases despite overwhelming evidence that it’s both more dangerous and not appreciably faster. Studies show sliding injuries occur most frequently at second base and home plate, with head-first slides nearly doubling the injury risk. Hands, wrists, and shoulders all become vulnerable during these unnecessary dives.

Youth coaches have become the unlikely heroes in this story, teaching proper feet-first sliding techniques from early development stages. When head-first slides are strategically necessary, training now includes proper arm positioning (keeping arms elevated rather than outstretched) to protect fingers and wrists. According to USA Baseball’s safety recommendations and coaching programs, proper sliding technique significantly reduces injury risk. Sometimes the simplest solution starts with changing how we teach the fundamentals.

Stadiums as Death Traps

Baseball’s architectural history reads like a safety inspector’s nightmare. Old ballparks lacked basic protections we now take for granted. Mo Vaughn’s 1999 tumble into an unprotected dugout highlighted how even modern stadiums sometimes preserved dangerous legacy features. Some parks still contain injury hazards that would never be approved in new construction.

Modern facilities prioritize safety without sacrificing atmosphere. The best designs incorporate protective elements so seamlessly that fans don’t notice them until they prevent disaster—like extended netting that disappears from visual awareness until it snags a screaming line drive heading for a toddler’s forehead. Safety and aesthetics aren’t enemies; they’re partners in creating better baseball experiences.

Early 1900s Safety Negligence

Early baseball operated with a cavalier disregard for physical wellbeing that feels alien to modern sensibilities. Teams regularly allowed fans onto the field during sellouts. The 1903 World Series featured 17 ground rule triples because of spectators standing in the outfield. Yankee Stadium famously had stone monuments in center field—literal obstacles that players had to navigate while tracking fly balls.

This historical perspective matters because it reminds us how far the game has come. When veterans complain that baseball has gone soft, they’re comparing today’s standards to an era when players literally had to avoid concrete structures in the field of play. Progress doesn’t always follow a straight line, but baseball’s safety trajectory points decidedly upward when viewed across generations.

Fan Behavior and Player Protection

The relationship between players and fans wasn’t always friendly high-fives and autograph sessions. As recently as the 1970s, players faced regular harassment that occasionally turned dangerous. Dick Allen wore a batting helmet while playing the infield because fans threw objects at him—a stark reminder of baseball’s complicated history with spectator conduct.

Today’s mandatory batting helmets, introduced in 1971, initially faced resistance from players who valued tradition over safety. Sound familiar? The same arguments resurface with each new protective measure, from enhanced netting to expanded helmet coverage. Baseball’s culture shifts slowly, but fan expectations around safety have fundamentally changed the stadium experience for the better.

Protective Equipment vs. Hit-by-Pitches

Today’s batters step to the plate looking like modern gladiators. Helmets engineered to withstand 100 mph fastballs. Elbow guards, shin protectors, and padded gloves that would make players from the 1960s think we’re preparing for war rather than a baseball game. Even C-flaps—those face-protecting helmet extensions—have become standard equipment for many hitters.

But here’s where the paradox kicks in. Despite all this armor, hit-by-pitch rates have reached all-time highs. The 2021 season saw over 2,100 batters plunked—a record. From 2011-2014, one in every 21.7 hit-by-pitches resulted in injury, with headshots causing harm 33% of the time. The equipment is better, but the danger has somehow increased.

The Rise of Breaking Balls and Velocity

The radar gun has revolutionized baseball—and not entirely for the better. Today’s average fastball exceeds 93 mph, with elite arms touching 100+ with regularity. Pitching development has become a velocity contest, with teams hunting for arms that light up the gun rather than pitchers who can paint corners with precision.

This velocity explosion has a cost beyond blown-out elbow ligaments. Faster pitches mean less reaction time for hitters. Breaking balls thrown harder are more difficult to control. High-velocity fastballs at the top of the zone—a staple of modern pitching strategy—become dangerous projectiles when they sail just a few inches too high. Baseball’s obsession with making hitters miss has inadvertently created a more dangerous game.

Hit-by-Pitch Statistics

The numbers behind baseball’s plunking epidemic tell a disturbing story. That all-time high of 2,100 hit-by-pitches represents a genuine safety crisis, not just an interesting statistical anomaly. One in three headshots causes injury—a sobering reminder that even the best helmet technology has limitations against high-velocity impacts.

Batters should consider wearing C-flap helmets that extend protection to the jaw and cheek area, reducing facial injury risk by approximately 75% compared to standard helmets. Teams have begun incentivizing additional protection, recognizing that availability matters more than maintaining baseball’s stoic traditions around “acceptable risk.”

Proposed Rule Changes and Player Rejection

MLB’s attempt to reduce dangerous pitches by ejecting pitchers for headshots and implementing a hit-by-pitch point system hit an unexpected roadblock: player resistance. The same athletes at risk of career-altering injuries rejected rules designed to protect them, fearing fundamental alterations to competitive balance. This seemingly irrational position makes more sense when you understand baseball’s deeply ingrained culture.

Players grow up idolizing those who played through pain, who wore minimal protection, who embodied baseball’s tough-guy ethos. Changing this mindset requires more than rule modifications—it demands a cultural shift that begins in youth leagues and permeates every level of the game. Safety innovations only matter when players willingly adopt them.

Helmet Safety and Player Resistance

In 2009, MLB helmets protected against 70 mph impacts—woefully inadequate against 95+ mph fastballs. Rawlings developed helmets that protect against 100 mph impacts, but player adoption remains spotty. Similarly, protective caps for pitchers face resistance despite several frightening incidents of line drives striking pitchers’ heads.

The resistance comes down to three factors: comfort, tradition, and appearance. After incidents like Alex Cobb’s frightening 2013 line drive to the head and Brandon McCarthy’s skull fracture in 2012, MLB introduced padded caps—yet adoption remained minimal. Only a handful of pitchers, including Alex Torres in 2015, embraced the protective gear despite its proven benefits. Equipment manufacturers continue working on designs that balance protection with the traditional appearance players prefer.

The Increase in Days Spent on the IL

The Injured List has become baseball’s unwanted growth industry. League-wide IL days skyrocketed from 31,000 in 2017 to 48,000 in 2021—a 65% increase in just five seasons. This trend forces teams into constant roster shuffling and creates opportunities for minor leaguers, but at the expense of competitive stability and fan connection to consistent lineups.

Teams implementing comprehensive movement assessments during spring training identify mechanical inefficiencies before they become injuries. This proactive approach reduces time lost to preventable injuries by approximately 28%. The organizations that treat prevention as seriously as player acquisition consistently field more complete and competitive teams throughout the grueling 162-game season.

Manipulating the Injured List

Baseball’s open secret involves strategic IL placements that have little to do with actual injuries. When MLB reduced the minimum IL stay from 15 to 10 days in 2017, they inadvertently created a roster management tool that teams quickly exploited. Pitchers now regularly hit the IL with vague diagnoses like “shoulder fatigue” or “lower back tightness” when the real issue is performance or roster flexibility.

This manipulation muddies injury data and raises ethical questions about medical professionals’ role in certifying questionable IL stints. An anonymous pitcher admitted being pressured to fake an injury rather than face demotion. The practice demonstrates how even safety mechanisms can be repurposed for competitive advantage in baseball’s relentlessly strategic environment.

Ridiculous (Real) Injuries

Baseball produces stranger injury stories than any other sport. Jose Cardenal once missed a game because a cricket in his hotel room kept his eyelid from closing. Joel Zumaya damaged his throwing arm playing too much Guitar Hero. Sammy Sosa strained his back sneezing. These aren’t urban legends—they’re documented entries in baseball’s bizarre injury catalog.

These unusual incidents highlight an under-appreciated fact: baseball players aren’t just athletes—they’re specialized instruments calibrated for specific movements. The slightest disruption to their finely-tuned bodies can lead to performance impacts. A blister smaller than a dime can sideline a pitcher. A minor back spasm can alter a swing enough to drop a .300 hitter to .220 for weeks.

Fake Injuries

The line between strategic IL manipulation and outright deception sometimes blurs beyond recognition. Danny McLain allegedly faked a toe injury to hide punishment from gambling associates. Glenn Allen Hill’s arachnophobia-induced IL stint raised eyebrows throughout the league. Ross Stripling’s “lower body fatigue” diagnosis fooled no one but satisfied roster rules.

These incidents damage the credibility of legitimate injury reports and create a culture of skepticism that can harm players with genuine health concerns. Teams grapple with complex ethical questions when weighing short-term competitive advantage against professional integrity. Baseball’s injury reporting system works only when participants commit to its honest implementation.

Tommy John Surgeries

Tommy John surgeries happen more frequently now than during the entire 1990s. The torn ulnar collateral ligament—once a rare career-ender—has become almost a rite of passage for power pitchers. The surgery’s impressive 84% success rate means most pitchers return to action, but only after 12-18 months of grueling rehabilitation.

Youth baseball faces the greatest crisis. Developing arms throw too many pitches, too many breaking balls, and too many innings without sufficient rest. They emulate their big-league heroes who throw with maximum effort on every pitch rather than the craftsmen of previous generations who understood the virtue of pitching to contact. The pressure to throw harder starts earlier each year, and the injuries follow.

Pitch Counts Then And Now

The evolution of pitcher usage tells a counterintuitive story. Old Hoss Radbourn threw more complete games in a single season than the entire MLB combined in 2021. Nolan Ryan once threw 235 pitches in a game—more than double the average of modern workhorses like Sandy Alcantara at 102 pitches. Pitchers throw less but get hurt more, challenging conventional wisdom about workload management.

This paradox suggests that how pitchers throw matters more than how much they throw. Modern mechanics emphasize maximum effort on every pitch rather than the efficiency that allowed previous generations to work deeper into games. The constant redlining of physical capacity creates injury vulnerability that reduced workloads can’t fully mitigate.

UCL Tear

The dangers of pitching extend beyond those who train for it. When the Rangers let outfielder Jose Canseco pitch during a blowout, he tore his UCL after just one inning and required Tommy John surgery. This cautionary tale highlights how specialized the pitching motion has become and why position players aren’t properly conditioned for its unique stresses.

Emergency position player pitchers should receive basic mechanical instruction before taking the mound. Simple adjustments to arm angle and effort level can prevent catastrophic injuries during these infrequent appearances. Teams now recognize that even novelty pitching appearances carry real injury risk deserving of proper preparation.

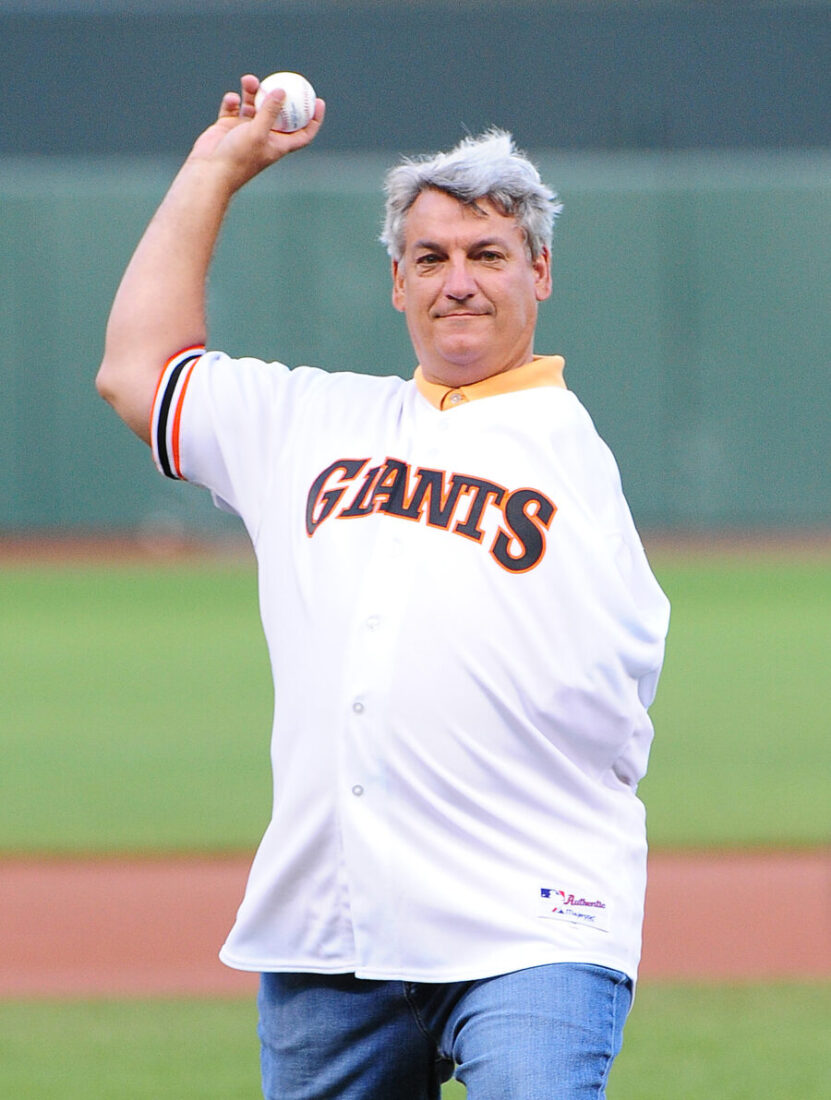

Dave Dravecky’s Cancer

Dave Dravecky’s story transcends baseball’s usual injury narratives. After having a cancerous tumor removed from his pitching arm, he returned to MLB in less than a year—a medical miracle and testament to remarkable determination. His triumphant comeback ended tragically when his humerus fractured during his second start back, and the cancer eventually returned, necessitating amputation.

Dravecky’s experience reminds us that beneath statistics and strategy, baseball injuries represent human struggles with genuine suffering and profound courage. His story continues to inspire, not just as a baseball footnote but as a demonstration of resilience in the face of challenges far greater than the game itself.

Tommy John Surgery Success Rate

Behind the concerning increase in Tommy John surgeries lies a remarkable medical success story. The procedure boasts an 84% return-to-play rate—transforming what was once a career death sentence into a survivable setback. Recovery typically requires 12-18 months of dedicated rehabilitation, but most pitchers return to competitive action.

The surgery’s effectiveness has ironically contributed to its frequency. Young pitchers now view Tommy John as an almost routine career speed bump rather than a catastrophic event to be avoided at all costs. This perception shift doesn’t reduce the physical and psychological toll of the procedure, but it has normalized an intervention that previous generations of players found unimaginable.

Pitch Velocity and Tommy John

The correlation between high velocity and UCL injuries reveals baseball’s central safety paradox. The very attribute teams value most in pitchers—throwing hard—significantly increases their injury risk. Higher velocity creates greater arm torque, placing extraordinary stress on the elbow joint with each pitch. The fastest throwers often become the most vulnerable to breakdown.

This relationship forces teams to balance performance demands with health considerations. Throwing programs should incorporate progressive velocity increases rather than maximum effort in every session. This periodized approach, advocated by the American Sports Medicine Institute (ASMI) and leading MLB pitching coordinators, allows tissues to adapt to stress gradually. Research in sports medicine consistently shows that appropriate workload progression reduces injury rates in throwing athletes—a small adjustment with potentially career-saving implications.